Directives Toward the Practice of Biblical Worldview Integration

How professors view the world is how students will begin to see the world.

The ultimate focus of biblical worldview integration is for the next generation.

Introduction

A Gen-Z influencer from England, Freya India, says we have lost human connections, saying we are “products with labels.” Knowing something is missing, India explains,[1]

This is part of a deeper instinct in modern life, I think, to explain everything. Psychologically, scientifically, evolutionarily. Everything about us is caused, categorized, and can be corrected. We talk in theories, frameworks, systems, structures, drives, motivations, mechanisms. But in exchange for explanation, we lost mystery, romance, and lately, I think, ourselves.

The therapeutic “new religion” has not been enough, according to India.[2] In another writing, India says her generation “has been trained to doubt” and rejoice in others’ uncertainty. “We live in a culture of doubt” India admits. Fascinatingly, there is a tertiary biblical admission: “Doubt is a dangerous thing, more dangerous than we think. Doubt is the first feeling before the fall, the beginning of destruction.”[3]

Derek Thompson knows that something is missing and blames the phenomenon on a “churchgoing bust.” Derek, an agnostic, laments,[4]

I wonder if, in forgoing organized religion, an isolated country has discarded an old and proven source of ritual at a time when we most need it. Making friends as an adult can be hard; it’s especially hard without a scheduled weekly reunion of congregants. Finding meaning in the world is hard too; it’s especially difficult if the oldest systems of meaning-making hold less and less appeal. It took decades for Americans to lose religion. It might take decades to understand the entirety of what we lost.

Culture is bereft of answers to address perennial problems about relationships, individual purpose, faith, and community. In the university we are confronted by these as well as a multiplicity of topics including curricula, assessments, artificial intelligence, censorship, academic freedom, intellectual property, or fiscal stewardship. Christian universities are preparing their students to think biblically in a constantly changing world with difficult problems and tenuous solutions. The practice of Christian faith-learning integration[5] depends on doctrinal pillars, overarching umbrella principles, methodology, apologetics, and instructional methods, all reliant upon biblical directives.

1. Doctrinal pillars

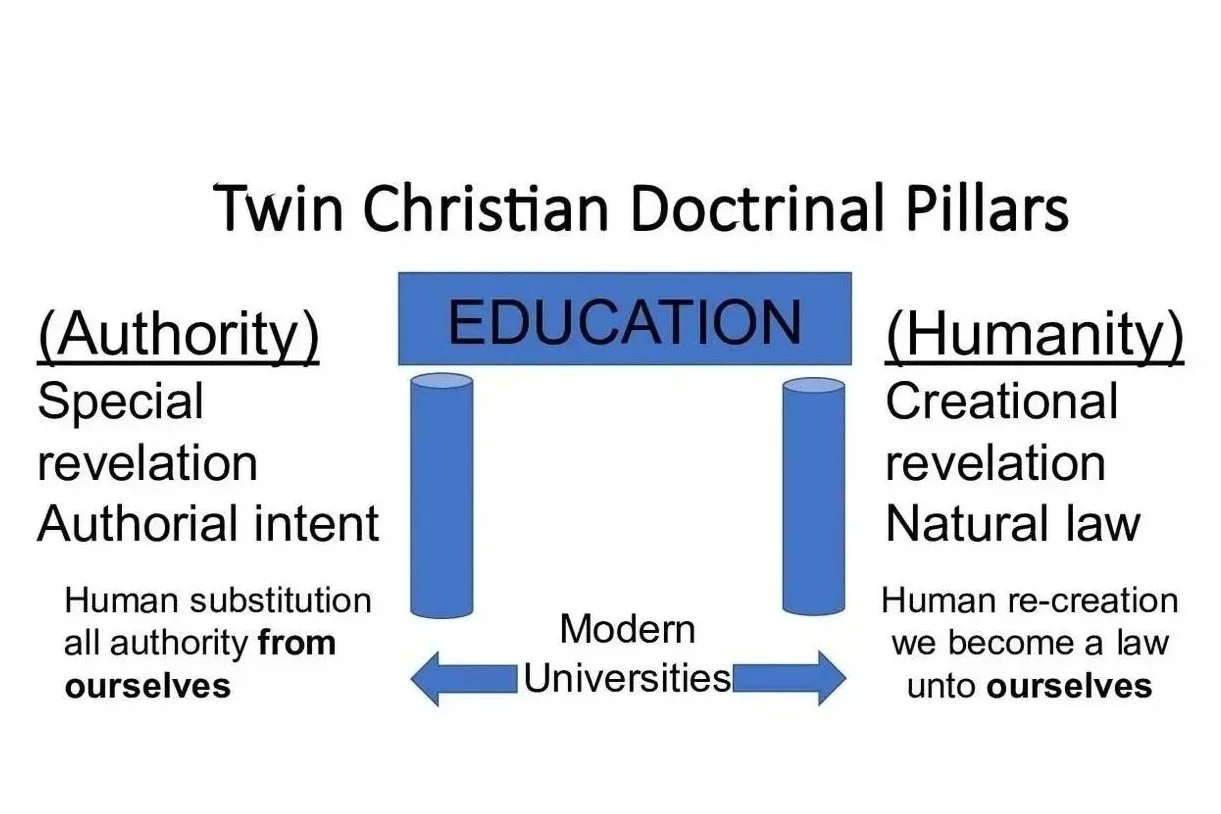

Figure 1

During my days of earning a M.A. in English at IUPUI (now Indiana University Indianapolis), then being invited to teach there in the humanities (2016-23), I learned a great deal about the modern public university. In short, the doctrinal beliefs of the university were in direct contrast to my Christian worldview in two essential categories: authority and humanity (Figure 1). The transcendent authority from God and His Word[6] has been replaced with human-centered authorities (individuals or institutions, cultural fixation or community identification). The human person, a creation of The Creator, subservient to creational revelation and natural law, is no longer identified by God’s image but rather society’s image (material over immaterial, experiential over theological).

Some may not be surprised by this finding. What may be surprising, however, is the thought that every single educational discipline, process, or curricula abides by authority and humanity. A simple example is a course syllabus. The written course program is authoritative, telling professors and students what is expected. Educators and students comprise the humanity who will accomplish the requisites. Within the structure of a teaching institution, all are under the authority of another,[7] at the same time stipulating that humans are equal because of our Divine image bearing.[8]

Answering the two questions, “Who says?” and “Who are we?” acknowledges our worldview. Hebraic-Christian authority structures give the basis for what has been called “biblical integration,” the essence of what it means to teach Christianly. The Christian life is governed by a belief system; how I view reality depends upon my doctrinal “glasses.”[9] Scripture demands doctrinal regularity and accountability. Doctrine forms the basis for application.[10] And lest we forget, doctrine should be internalized, affecting our affections.[11] Students in my Gothic horror literature class, for instance, would be asked about doctrine through affective questions. Each query is burgeoning with creaturely concerns:

How has your attitude changed?

How have you been internally motivated?

What virtues should you display?

How has this experience brought you joy?

How have you been caused to resolve anything in your life?[12]

Further, doctrine should matter to faculty in aeronautics when they consider flight is possible because of The Creator and His creation. Jeremiah 33 assumes the creative process using the words, “made,” “formed,” “established,” “appointed time,” and “fixed laws.”[13] The affective educational response is no different in the sciences than in the humanities. The English words “marvelous” or “wonderous” suggest something extraordinary, amazing, or causing astonishment. While the physics of creation can be appropriated for human use, it is the metaphysics which allows believers in any venue to exclaim, “You would not believe even if you were told.”[14]

Our collective wonderment at the created order explains our position as image bearers. Those dedicated to a naturalistic view of life, on the other hand, will focus on the external. Exclusive attention paid to fashion, exercise, longevity, or health care – none of which are wrong or bad in and of themselves – often overtakes, even eliminates, any concern for what makes us people with an explanation of why people’s physical lives matter. The consequence of a naturalistic universe – in contrast to a Designed universe model – becomes utilitarian[15] when it comes to the treatment of human beings over concerns about, abortion, bullying, freedom of speech, treatment of the poor, racism, agism, or any social issue.

From a decidedly Hebraic-Christian point of view, protecting all humans in and out of the womb, pushing back against the propensity of inherent human corruption,[16] is based on the authoritative Truth of Scripture. Biblical law codes form the foundation for any discipline creating two pillars that sustain how best to live in God’s world.

2. Umbrella principles

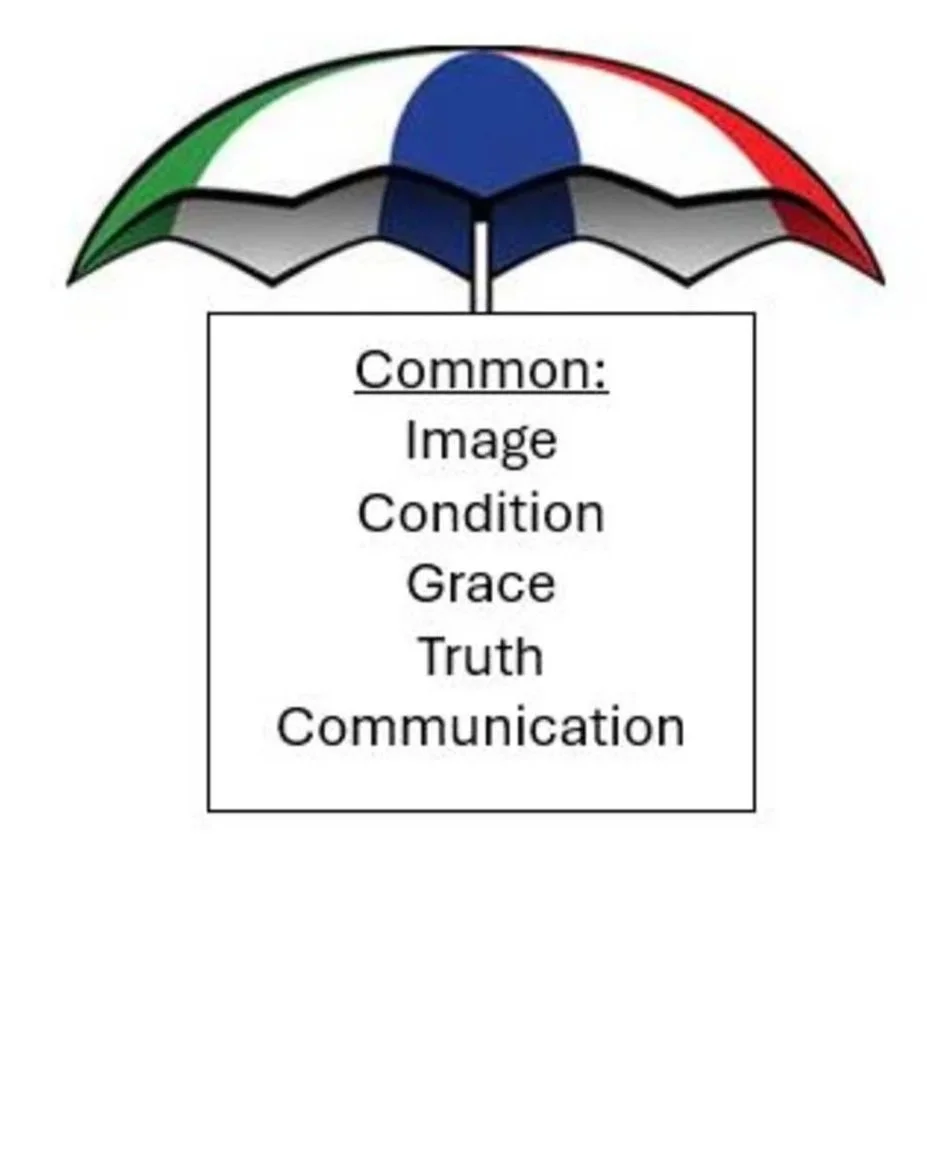

Figure 2

The creation of diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) programs in the public university are fashioned upon human-centered declarations of who is and who is not accepted. Distinctively, it is God’s image in humanity which creates the possibility of inclusion for everyone. The exclusivity of biblical truths about authority and humanity are the only possibility for inclusivity.[17] Humans bear a common heritage, “one blood,”[18] all emerging, from a Christian vantage point, as humans made in God's image. When it comes to faith-learning integration, our commonality as a species suggests at least five umbrella principles (Figure 2). By umbrella I mean our overarching shared aims, no matter where we live, no matter when we live, no matter from what culture we arise.

The first, most obvious commonality, emanates from our concerns, already expressed, about humans being made in God’s image. First Testament teaching is clear. Our unique creaturely standing assumes equality of persons no matter our ethnicity, nationality, economic status, nor education level. Equality should produce equal opportunity, standards of justice applied to all, ethical codes employed the same to everyone, recognizing that in a fallen world, ultimate recompense will come in the next life.[19] The impact on coursework in every field, from the humanities to the sciences, is felt through the application of biblical analysis.

A second commonality is our condition, our sinfulness. Since Adam rejected the original standard – “But of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil you shall not eat” – The Almighty’s intention is affirmed through law codes beneficial for all humanity.[20] “By what standard do I judge?” is a ubiquitous concern, which follows the earlier question, “Who says?” Every story must have some measurement of goodness. Scientific discoveries must be verifiable based on protocols. Syllabi set requirements. Business offices have codes of conduct. But humans are prone to reject rules and sidestep standards because of our corrupt nature. So, the necessity of standards is everywhere present, a worldwide commonality. Scripture says, "Your laws endure to this day, for all things serve you" and "He set them in place for ever and ever; he gave a decree that will never pass away."[21]

Universal regulations suggest the necessity of coherence, something that holds everything together, a third commonality shared worldwide. Scripture is clear that Jesus is the one “who holds all things together.”[22] How does everything fit? How does life make sense? There must be an intersection and unification of heaven and earth, supernatural and natural. From the very first statement in Scripture, unity and wholeness were necessary — “the heavens and the earth” meant “everything from A to Z” in the Hebrew mindset.[23] Both believers and unbelievers in scripture, identify the Hebrew God as the God of all gods. That is, he is the one and only true God. And according to Scripture, we have pagan kings, prostitutes, and Israelite kings all saying the same thing, that this God holds all things together.[24]

Common grace is the fourth connection among all persons everywhere. The goodness of all creation benefits all people. And the scriptural emphasis is always about God's beneficence to everyone because he cares about humanity. And this goodness comes to us in things like the weather or language or agriculture.[25] The concept of common grace allows believers and unbelievers alike to study creation. In academics, no matter our disciplines, the data, properly adjudicated, display common grace truths.

Since professors can study together, there is a need for communication, a fifth common principle impacting everyone. Language opens dialogue. It allows us to be intentionally connected. Humanity was originally created to be co-creators in God’s world; the Genesis 1:28 commands manage and conserve[26] were never rescinded. Human image bearers communicate not only with God but with each other. Learning somebody else's language is an act of love, an act of understanding that we are not in this life by ourselves. This, of course, gives us the basis for understanding that believers have a responsibility to communicate the gospel to all nations.[27]

The umbrella principles of common image, condition, grace, truth and communication allow for the pursuit of our studies to be a constant delight.[28]

3. Educational Approaches

My class was discussing the concept of love. We were examining love’s source definition, application, goal and result. We even used ideas from children's books that might be read by second graders.[29]

The students in a public university course relished the discussion. They were talking about all aspects of love that might concern them. Then I paused, as we had an opportunity to make a segue in our communication. I said, "You do realize, don’t you, that when people talk about love, you might be talking about people who take love in a very different, violent kind of way."[30]

The students were taken aback by this, not realizing that some people, as they define love, don't define love as others define love. The point is that the definition of love, the source of love, and its application matters especially from a Hebraic-Christian point of view. It is incumbent upon professors to consider the importance of words, getting students ready for the world in which they will be invested.

Extending the teaching, a biblical view of love emphasizes an unconditional quality. Far beyond contractual, transactional obligations, we are covenantally loyal to family, friends, colleagues, even our vocational opportunities. In this sense, we bear responsibility for person-to-person and person-to-institution relationships. A biblical view of love indicates a covenantal loyalty—a commitment no matter what.[31]

Defining our discipline may include the educational approach beginning with the history of what we study. Those who teach physics, for instance, teach a millennia old subject. Sociology, on the other hand, is quite a new discipline. Does the history of physics or sociology, impact how we study them? Might the history of either be directed by a worldview that is informed by proponents who may hold antithetical views to a Hebraic-Christian point of view? Can we trace the discipline’s development and intersection with Christian thinking? Investigations such as these could be the scope of student assessments.

Another avenue of discipline-specific study includes hermeneutics. How do we interpret our disciplines? For instance, as a theologian, I'm going to have a different kind of hermeneutic than the sociologist, biologist, or social worker. Each discipline is understood and interpreted from a different point of view or constructed by a different framework. Professors will need to help students understand that process. Are the interpretive lenses or the kinds of research accomplished in our disciplines important to evaluate Christianly? How does our viewpoint as Christians matter when it comes to analyzing, then synthesizing ideas?

The goal of our discipline may be influenced by our interpretation of it. Where does this focus of study lead? For instance, if you're going to address the question of student debt, personal responsibility should be a filter. Ownership of the debt comes into question. Justice issues concerning overcharging or exorbitant interest could come into play. Ultimately, then, the question becomes: in business or finance or commerce, what is the goal of your discipline? When we discuss money, who bears the responsibility of stewardship?

Ultimately, our study, whatever it is, will have a result, an outcome, which that discipline will produce. Compare two movie examples: Eat Pray Love and Cabrini. The two movies have a very different point of view. Eat Pray Love emphasizes the consistent concern “as long as you're happy.” Cabrini is quite different, distinctive, with a Christian view where the focus is on others.

Figure 3

The compare and contrast approach to any topic helps students consider a choice as we teach them to think Christianly. Worldview development as Christians can begin with Genesis 4 (Figure 3). In Genesis 1 and 2, we understand that all things were intended by God to be good. Genesis 3 records the human decision to rebel against The Creator. Immediately after, the human story is mirrored in every individual and institution. People choose the way of Cain or the path of Abel.[32] A simple diagram of Genesis 4 is a microcosm of every person and every worldview.

Our fields of study are quite different from each other. However, there are universal approaches to our work. Each discipline is responsible to define and interpret, find the source and age, while focusing on the goal and outcome of our classes. Whether we utilize direct instruction, reading, research, collaborative projects, or various assessments we can facilitate Christian thinking for our students.

4. Apologetic Intersections

One of the biggest issues I confronted when teaching in a public university was the issue of origins and ends. I would have long discussions with my colleagues about what we believed and where our beliefs might take us. We all seemed to agree on the ends. We wanted justice, we wanted peace, we wanted creation-care. But the real question was the question of origins. Where do any of our desired results originate? If I have a source of truth that's different than yours, what kind of end will that produce? The origin of ideas, where something comes from, the source of authority, was something about which we totally disagreed.

I would often say to my public university colleagues, unbelieving folks tend to lean on the Christian worldview for answers of ethics because a naturalistic point of view begs the question of “Who says?” or “Who decides?” I would ask, “What is the standard for justice?” or “By what means can the university stand against discrimination?” or “Why is stealing ideas from another person wrong?” We all agreed about what is unethical but disagreed as to the source of such a declaration.

In the Christian university, professors want to help students understand that answers to such questions have a biblical basis. In this way, faith-learning integration includes apologetics, a defense of the Faith. Discussing origins and end is a good place to begin.

The best explanation for the results we desire, comes from the God whose original intention was for the good of His creatures and creation. It is the question I ask of those who may agree with good outcomes but disagree about where those come from. And then there is the question of ethics. How do we know the ethical way to get to the outcomes we desire? Over the years, I have reduced the idea to this mantra: knowing where you’ve come from, and where you’re going to, helps you know how to live now.[33]

Figure 4

Figure 4 displays the soil from which ethical fruit is grown. Worldview questions about God, creation, humanity, purpose, and yes, ethics, must have substantive authority. All kinds of philosophical questions confront students in their disciplines. Professors bear the responsibility to show the origin of the desired philosophical answers have theological roots. Good roots help bear good fruit. Notice the necessary words below the tree: transcendence, creator, eternal, providence, beneficence. Each doctrine exists in the Person of the God of the Bible. More doctrines could be addressed. However Christian professors must help students to understand that the fruit of our study comes from a theological root.

Consider one application: creation-care. Following God’s commands for earth-keeping provides nourishment for all. Careful attention to property is commanded. During Israel’s captivity in Babylon, God’s orders were to “plant gardens and eat what they produce,” building prosperity for individual and nation alike. Obedience to God and fruitfulness of the land were intricately tied together. Prosperity produces the possibility of private property development. Love of the soil spurred Uzziah’s land development which provided work for people and cultivation of the land. Ownership provides for a flourishing economy. The earth was given to humanity for cultivation and enjoyment. Property given to another is passed on to succeeding generations, as an inheritance. What is passed on as an inheritance is based on an ancient and permanent right, or a person’s heritage. Biblical principles drawn from this overview of heritage include: (1) all possessions are given by God; (2) possessions are not a result of reward but given freely by God; (3) property rights were a way of people attaining wealth, providing for family, and were protected by law; (4) there is an eternal nature to one’s inheritance—it cannot be taken away; (5) responsibility for protection lay with the human as caretaker of the heritage.[34]

Apologetic intersections, giving a reason for Christian beliefs, can be established in every university discipline. The believing professor bears the responsibility of thinking, then teaching Christianly, so that students can see biblical worldview integration in action.

5. Curricular methods

An airport billboard bore the picture of a doctor kissing the forehead of a child with the caption, “Science creates hope.” Can science, a discipline that bears the responsibility of making observations in the physical world, “create hope”? Science doesn't create hope, it doesn't create truth, it cannot create ethics. Science is concerned with the natural world. Hope has supernatural origins.

Figure 5

Displaying a picture of the airport billboard would be a powerful opportunity for students to discuss how to think Christianly about the ideas they see around them. A fifth construct in faith learning integration is methodologies used in our curriculum. Figure 5 communicates what happens when another worldview takes a piece of biblical truth then makes it into another truth altogether. Notice what happens in the figure. The red dot is one piece of truth. As the subtitle suggests, the biblical ideas of “human” or “natural” or “authority” may be taken as a whole, making it the whole truth of their worldview: humanism, naturalism, authoritarianism (the suffix indicating a philosophy or worldview). The diagram may be a helpful way for our students to understand how we think differently as Christians.

Another method employed in the classroom may be to set the results of two worldviews side-by-side, simply comparing what somebody else believes. A chance universe versus a designed universe, for instance, displays very distinctive points of view. Reality is constructed from eternal matter in naturalism or from an Eternal God in the Hebraic-Christian perspective. Replicate any worldview question about reality, God, humans, knowledge, or ethics to help students to understand how to think Christianly in their classrooms.

Sometimes we want to flip the script. There might be two parts to an idea. So, for instance, a student might desire to write an essay on global warming and climate change. The professor could then ask, “What are we not hearing? In all your research, is there a point of view not represented?” If only one side of an issue is being presented, flip the script to address alternative theories or discover new ideas.

A Christian point of view about reality, ethics, or purpose could be simply composed by observing observations from Genesis 1:1 through 2:3. Simply observing the wisdom that God has established in his world such as beauty, appreciation, form, function, harmony, energy, or variety in those verses would generate all kinds of ideas which would be helpful for students to unpack on the road to thinking biblically about their subjects.

Conclusion

Five areas of Biblical worldview integration might be helpful in class construction: doctrinal pillars, umbrella principles, educational approaches, apologetic intersections, and curricular methodologies. The practice of biblical worldview integration depends on lenses, the spectacles through which the world is viewed. How Christian professors look at their world is going to impact the way students look at theirs. Discussion questions give an opportunity to further consider how the Christian professor might begin the process of thinking and teaching Christianly.

How can faculty better support students in biblical worldview integration? How can assignments be created that will assess student worldview thinking?

How should faculty deduce truth and error as they study and teach their discipline? How do research findings point toward supernatural truth?

How does special and creational revelation help faculty interpret information with other disciplines? Is there an opportunity for team-teaching or cross-disciplinary engagement that might point at true Truth in God’s world?

How can faculty identify teaching methods that help the practice of biblical worldview integration? Have faculty considered the importance of wedding the content of their discipline with the communication of it?

When faculty read in their discipline are they asking how their subject applies in the world? Is classroom work shown to be connected to the culture and context of a student’s world?

[1] Freya India, “Why No One has a Personality Anymore,” https://www.freyaindia.co.uk/p/nobody-has-a-personality-anymore.

[2] Freya India, “The New Religion is not Enough,” https://www.freyaindia.co.uk/p/our-new-religion-isnt-enough.

[3] Freya India, “Why We Doubt Everything,” https://www.freyaindia.co.uk/p/why-we-doubt-everything.

[4] Derek Thompson, “The True Cost of the Churchgoing Bust,” Atlantic (April 3, 2024), https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2024/04/america-religion-decline-non-affiliated/677951/.

[5] I will be using the phrases “faith-learning integration,” “biblical worldview integration,” and “biblical integration” interchangeably since Christian universities utilize different nomenclatures to describe the process of allowing biblical principles to permeate subject areas.

[6] God is the arbiter of truth from His Word because, “God doesn’t lie or change His mind” (Num 23:19;1 Sam 15:29 and Mal 3:6). And “His works are perfect, his ways are just, a faithful God who does no wrong, upright and just is he” (Deut 32:4). Further, “The God of Truth” (Isa 65:16, that is, Truth has its origin in God) has eternal righteous laws (Ps 119:160) resulting in the Christian education phrase, “All Truth is God’s Truth (Ps 119:152, 160; 1 Kings 3:1-15; 4:29-34; 10:1-9).

[7] From Scripture to the mission to board to administration to faculty to curricula to syllabi to assignments to grading to treatment of our students, all are issues of authority. And in contradistinction to the cultural dictate “respect is earned,” Scripture is clear: respect is given (1 Thess 5.11-12, Heb 13.7, 17).

[8] Scriptural conclusions about our personhood arise because we are made in God’s image (Gen 1:26, 27; Ps 8:5-8; 1 Sam 16:7; James 1:27; 3:9; 1 Pet 3:3-4). Genesis establishes (1) people were given special consideration (Gen 1:26-27) where three times the word “created” was used of humanity for emphasis; (2) humans were made on the sixth day, the pinnacle of creation; (3) human persons were given special attention (Gen 2:7) “God formed man from the ground,” “God breathed into man the breath of life”; (4) humanity was given a special “image,” the ancient Near Eastern word indicating the individual was operating based on the king’s seal from a signet ring (Gen 1:26-27; 5:3; 9:6; Matt 20:20-21). In that way, humans are God’s representation and representative on earth (Ps 8:5-8).

[9] The image of eyeglasses was used twice by John Calvin in his Institutes of the Christian Religion. “Just as old or bleary-eyed men and those with weak vision, if you thrust before them a most beautiful volume, even if they recognize it to be some sort of writing, yet can scarcely construe two words, but with the aid of spectacles will begin to read distinctly; so Scripture, gathering up the otherwise confused knowledge of God in our minds, having dispersed our dullness, clearly shows us the true God” (I.vi.1) and “For just as eyes, when dimmed with age or weakness or by some other defect, unless aided by spectacles, discern nothing distinctly; so, such is our feebleness, unless Scripture guides us in seeking God, we are immediately confused” (I.xiv.1).

[10] 1 Timothy 1:10-11, 15, 18; 2 Timothy 1:13-14; Romans 6:17; 2 Thessalonians 3:6.

[11] Christian university professors are encouraged to, “Look to the affections, the deep dispositions of the heart” to change their character by “active engagement with God and the world.” William C. Spohn, “Finding God in all things: Jonathan Edwards and Ignatius Loyola,” in Finding God in all things: Essays in Honor of Michael J. Buckly. S. J., eds. Michael J. Himes and Stephen J. Pope (New York: Crossroad Publishing Company, 1996), 249.

[12] Notice that none of these ideas (attitude, motivation, virtue, joy, resolve) can be seen or held in one’s hand. As I have written elsewhere, “You can’t see an attitude. You can’t touch an emotion. You can’t taste a mindset. But I can certainly experience attitude, emotion, and mindset in a person’s body language, tone of voice, or facial expression. In education we call this kind of learning affective. Learning that reaches to one’s thought process, that works to transform someone’s spirit, is affective learning.” Mark D. Eckel, “1 Essential Educational Practice: Reflection,” (December 13, 2022), https://markeckel.com/2022/12/13/1-essential-educational-practice-reflection/.

[13] Jeremiah 33:2, 20-21, 25-26. “Established” means to bring something into being with the consequence that its existence is a certainty. “Formed” suggests God’s personal interaction with His creation (Pss 33:15; 74:17; 94:9; 95:5; Jer 10:16; 51:19; Zech 12:1). “Made,” indicates these works are “great” (Ps 92:5), exemplified by a nation like Assyria being “a work of God’s hands” (Isa 19:25) as are humans (Isa 64:7,8). “Appointed time” means God maintains the seas and all that is in them “according to their proper times” (Ps 104:27). “Fixed laws” refers to decrees or regulations to which something or someone is bound; as Job 28:25, 26 says winds, waters, and storms are given by God.

[14] Habakkuk 1:5. Various Scriptures testify to the human responses of the extraordinary nature of God’s works (Gen 43:33; Ps 48:5; Ecc 5:8; Dan 11:36). Other observations include: (1) beyond human capabilities of explanation (Job 5:9; 37:5); (2) awakens astonishment and praise (Ps 98:1); (3) emphasis is not on the fact of the miracle itself but on God’s work in it (Ps 118:23).

[15] Utilitarianism means ethical decisions are based on the answer to the question, “What is the greatest good for the greatest number of people?” Individuals are reduced to collected data points rather than esteemed for their dignity.

[16] It is impossible to sketch the fullness of doctrinal teachings about humanity in this essay. However, human dignity is in tension with human depravity within individuals and institutions. While God’s image is maintained in the human person (Gen 1:26; 5:1) it is now distorted through the sinful father’s imprint (Gen 5:3; Rom 5:12). Humans are thoroughly permeated with evil from the intent of their thoughts (Jer 17:9-10) to the results of their actions (Titus 1:15-16). The conscience, still the standard of human judgment for those without special revelation (Rom 2:14-15), is warped, darkened, and hardened by sin (Eph 4:17-19). Thinking is so futile that anything “spiritual” cannot be fathomed apart from restoration of The Spirit (1 Co 2:14).

[17] As I have written in the past,” The idea that One Truth makes other “truths” possible is the only answer to the question “Who says?” If we begin with inclusivity, we are left with the unanswerable questions “To what are we included?” and then “Who decides who is included?” Inclusivity by itself is a human-centered belief — “I will declare what truth is.” The exclusivity of Jesus’ gospel — “I am the Way, the Truth, and the Life” — is a God-centered origin. If we want inclusivity – and we do – it only comes through the exclusive claim of Christ.”

Mark D. Eckel, “Toleration,” (January 9, 2019), https://warpandwoof.org/toleration/.

[18] Acts 17.26. There is much to say about the importance of “heritage” in Scripture, including the importance of genealogies beginning in Genesis 4 that link humanity, not only to forebears, but to the excitement of oneness anticipated in Jesus’ prayer (John 17:21), foretasted at Pentecost rectifying Babel (Acts 2, Gen 11), a forecast of reunification where in Revelation 5:9 “every tribe, language, people, nation” will be brought into The City where “the nations will walk” (Rev 21:24).

[19] “Until I understood their final destiny” (Ps 73:15-17) explains that justice denied on earth will be applied in Heaven. The classic passage on justice on earth is Isaiah 58-59.

[20] Genesis 2:16-17. Laws beneficial for humans (Deut 28:1-14) are lauded by neighbors (Deut 4:5-8) and is meant for all people (Micah 4:1-4), a result of the gospel’s transformative power, translated into any culture to “do good” (Titus 2:14; 3:1, 8, 14).

[21] Psalms 119:91; 148:6. God stationed unseen principalities, powers, or pillars ("endure," "set them in place," Job 9:6; Psalm 75:3) that permanently, continuously control the physical world as "laws" (God's sovereign reign over every ordinance of creation). He set regulations ("gave a decree") marking the legal rights (Job 38:10), administrative oversight (Job 38:33), and boundaries (Jer 33:25) of the sea (Prov 8:29; Jer 5:22), celestial bodies (Ps 148:6), and rain (Job 28:26).

[22] Colossians 1:17.

[23] Gordon J. Wenham, Genesis 1-15: Volume 1 (Grand Rapids: Zondervan Academic, 1987), 15.

[24] Believers and unbelievers alike declared The Hebrew God created and unified all things; from Rahab to Hezekiah to Hiram, king of Tyre. Prophets throughout Scripture declare the same—all things come from and are held together by Yahweh (Josh 2.11, 2 Kgs 19.15, 2 Chron 2.12; Neh 9.6, Prov 30.4, Isa 44.24).

[25] The goodness of all creation benefits all people. The Scriptural emphasis is on God’s beneficence and goodness in weather, language, discovery, agriculture (Gen 39:5; Pss 107:8, 15, 21, 31, 43; 145:9, 15-16; Matt 5:44-45; Luke 6:35-36; John 1:9; Acts 14:16-17; 1 Cor 7:12-14)

[26] Often translated “rule” and “subdue,” the words manage, and conserve give a fuller English language understanding to the original Edenic intention. “Rather than being banned from ‘interfering with nature’ we are encouraged to do good. God gives us responsibility and ability not only to care, but also to innovate within the context of his creation and his will.” David Wilkinson, The Message of Creation (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2002), 43.

[27] Common Communication Co-rulers of the world, God’s image bearers communicated with their Creator and each other. After Babel, language learning opens dialogue between people groups. Language learning helps to establish unified communication, opportunity for The Good News in our disciplines (Gen 1:28; 2:16-17, 23; 3:8; 12:1-3; Ps 96; 98:2-3; Rom 1:5; 16:26; Rev 5:9-10).

[28] Psalm 111:2.

[29] Eileen Hatch, Someone Loves You Mr. Hatch. Pictures by Paul Yalowitz (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1996).

[30] Without going into detail, it is important to notice Scripture does not shy away from referencing the depravity of the depraved (Gen 4:8; 6:5; 19:4-5; Rom 1:24-32; 1 Cor 5:1).

[31] A biblical view of love (source to outcome) originates in God’s love—unconditional covenantal loyalty (Ex 34:6-7). The Hebrew word most often used is chesed translated in English as “loving kindness,” “mercy,” or “charity.” There are two kinds of covenants in Scripture: conditional (“if you do this for me, I’ll do that for you”) and unconditional (“no matter what you do, I will do this”). Hebrews believed they should mirror the attributes of God shown in the unconditional covenant. “Covenant” meant sacrificial giving. People loving God meant continual obedient commitment (Deut 10:12-13). “Covenant people” were to care for their neighbors, loving them as they would love themselves (Eph 5:29-29) “loving the stranger in your land” (Lev 19:18, 34). Our view of God will be our view of others. “Loyalty” emphasizes faithfulness, staying with, not leaving, follow through, say you’re going to do something—do it. Importance of chesed begins and ends with our view of God. As He cares for us, we should care for others.

[32] Juxtapose what Scripture says about Abel (Matt 23:55; Luke 11:49-51; Heb 11:4; 12:24) with what is said about Cain (1 John 3:12; Jude 11).

[33] Mark D. Eckel, “The Bible on Origins & Outcomes,” (June 13, 2023), https://markeckel.com/2023/06/13/the-bible-on-origins-outcomes/.

[34] “Property,” (Prov 27:23, 27). “Captivity” (Jer 29:5,7). “Prosperity” (1 Kings 4:25; 1 Chron 27:25-31). “Uzziah” (2 Chron 26:10). “Economy” (Jer 39:10; 40:10; 41:8). “Enjoyment” (Ps 115:16). Inheritance (Lev 25:23, 28; Num 26:52-56; 1 Kings 21:3-4; Prov 13:22).

MARK ECKEL

Executive Director | The Center for Biblical Integration

Liberty University